Examining a material that built New York

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

October 28, 2021

As I write this blog Archtober—the annual celebration of architecture and design with activities, programs, and exhibitions across the city—is nearing its end, and I wanted to close the month of in-person and virtual learning activities by looking at some aspects of our city’s built environment. There are a lot of potential topics I could concentrate on: the South Street Seaport Historic District itself is a unique collection of 19th and early 20th century buildings representing over 200 years of mercantile architecture. The Museum’s collection and archive includes both building components from Lower Manhattan structures (both surviving and no longer extant) as well as photographs and other documentation of the changing physical fabric of the city. While looking for a theme I found myself drawn to one of the most humble and ubiquitous building materials: the brick.

Bricks have been a part of New York City history since Dutch settlement in the 17th century, with bricks used in the foundations and edifices of thousands of structures in the five boroughs. The brick-making industry that developed along the Hudson River illustrates the impact of New York City as a commercial center in the surrounding region, as well as the importance of the waterways that connect them.

Join me in this brief exploration at bricks in New York City and the Seaport, taking it—excuse the pun—brick by brick.

Dutch and New Netherland Bricks

“Yellow Bricks”, ca. 17th century-18th century. Clay. Gift of Mr. Francis Nunan Howard, South Street Seaport Museum 1975.069.0001-3

These handmade bricks arrived at the Seaport Museum in 1975 with a note stating “…collected in your area. These bricks were brought to Manhattan in sailing ships as ballast and sold as building bricks in the late 17th and 18th centuries.”

There is an often repeated anecdote about bricks in colonial America—that English and Dutch colonizers imported large amounts of bricks from Europe to their settlements. Along with providing building material for the colonies, these shipments of brick also supposedly provided ballast for the ships on their westward transatlantic trip. This assertion has been challenged by Fiske Kimball in Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic where he states that the story comes from a misinterpretation of the terms “Dutch brick” and “English brick” (which can refer to the size or bond of American-made bricks) and that brick importation was negligible or completely unknown in most American colonies. Kimball notes that New Netherland was the only exception, and that bricks were imported from The Netherlands starting in 1633; however, bricks were also being produced in the colony as early as 1628. The brick structures in New Amsterdam were made of domestic brick supplemented by European brick. By the latter decades of the 18th century, New York was producing enough brick to ship and sell them to other colonies along the Atlantic coast.

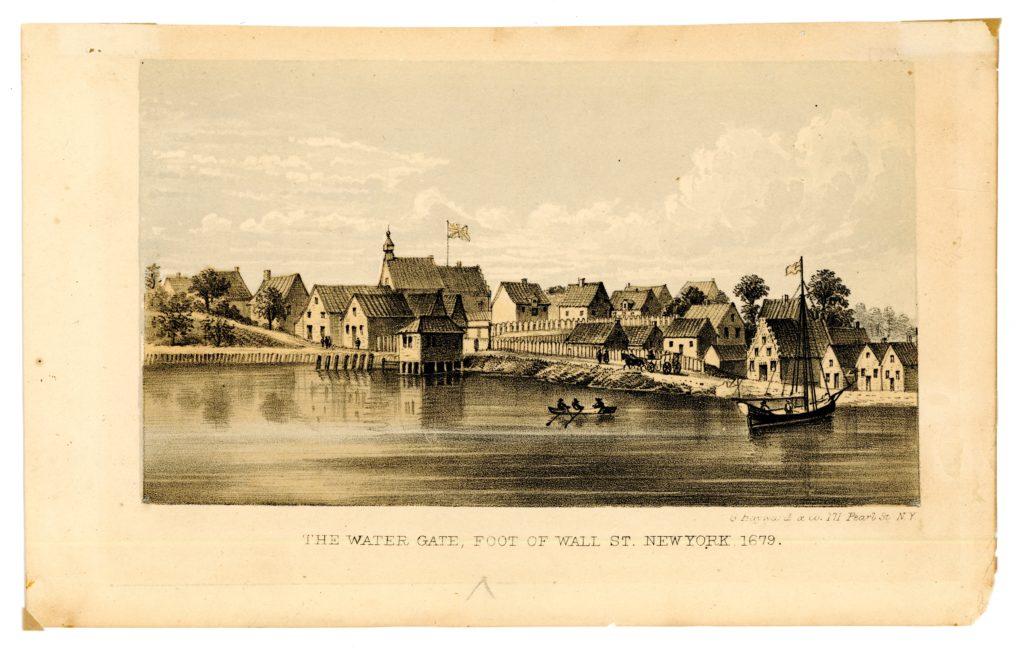

George Hayward & Co., lithographer. “The Water Gate, Foot of Wall St. New York, 1679”, 1876. Paper, ink. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.078.0033

Bricks were made by hand at this time. A basic summary of the steps in brick production starts with collecting the main ingredient: clay. Clay was dug out of an open pit and packed into a wooden brick mold which was left to dry. The bricks were then stacked and fired in large quantities at once, resulting in bricks of different quality based on where they had been placed in the kiln and therefore how they had been heated. Bricks from this time occasionally still have their maker’s preserved fingerprints visible on the surface. During the Dutch and English colonial periods, brick-making (and brick-laying) partially relied on the labor of enslaved Africans despite measures to exclude enslaved or free Black people from the trades.

Bricks of Schermerhorn Row (1810-1812)

I would be remiss if I didn’t write about the Museum’s current headquarters in the landmarked Schermerhorn Row. The Row was built from 1810 to 1812 as a set of counting houses that would provide all-in-one storefront, offices, and warehousing for businesses along the bustling East River.

The Row’s facades and party walls are hand-made brick and were likely produced and shipped from small towns along the Hudson River where large clay beds had been discovered (Hudson River brickyards would grow explosively later in the century as we’ll see later).

“Schermerhorn Row (4-12 Fulton Street), South Street Seaport Museum” ca. 1995. Photographic paper. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

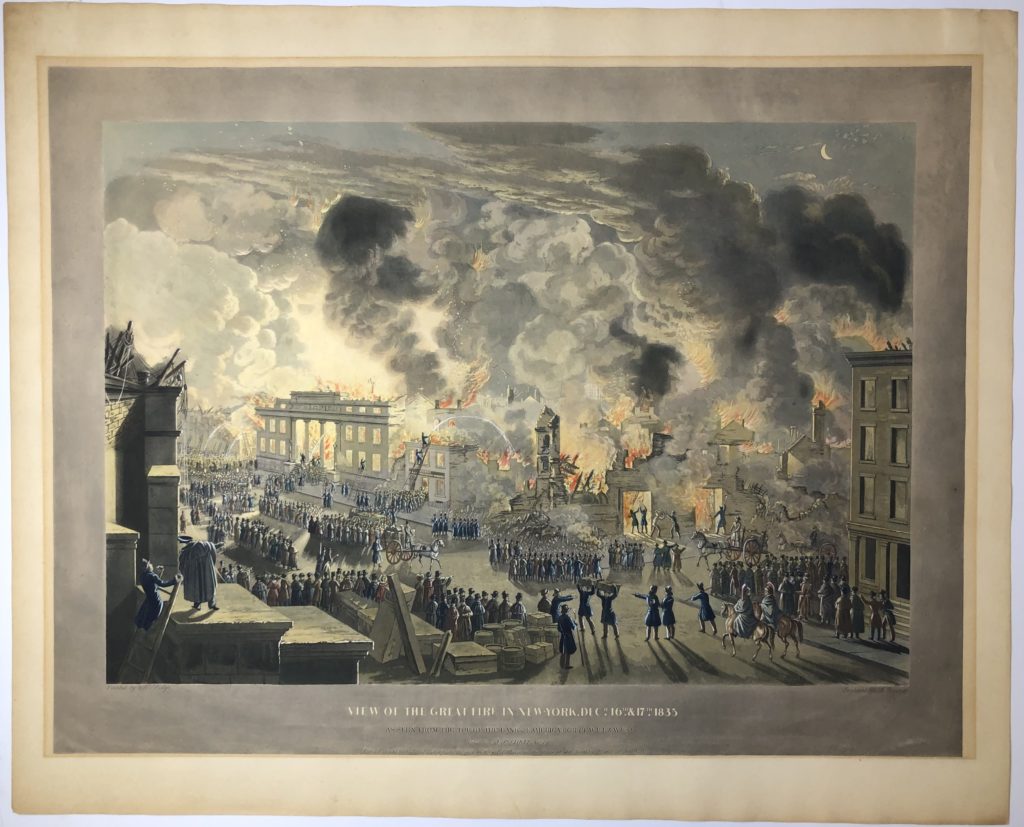

The choice of brick for Schermerhorn Row was typical, as merchants generally built with brick in New York City from the 1790s onward, and in fact required by the City as a fire-proofing method. Lower Manhattan would suffer a series of devastating fires in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that would destroy large swaths of the city’s colonial architecture. Recognizing the risk posed by wood buildings, attempts were made as early as 1766 to require brick construction in the densely populated parts of New York City.

Nicolino Calyo (American, born Italy, 1799-1884). William James Bennett (American, 1787-1844) “View of the Great Fire in New-York, Dec. 16th and 17th 1835”, 1836. Paper, ink. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 1991.070.0185

Though brick was a practical building material, it was not exempt from aesthetic concerns. The Schermerhorn Row facades show a level of care and finish not seen in the less public party walls between addresses. The facades employ Flemish bond, which alternates the long sides of bricks (stretchers) with the short sides (headers) along a single course. The Flemish bond was considered aesthetically pleasing due to its variegated pattern, but was acknowledged to be structurally poor, and difficult to lay, compared to other bonds. The party walls use the stronger and more practical Liverpool bond.

Left: Liverpool bond.

Right: Flemish bond.

If you continue to look at the exterior of Schermerhorn Row, and other brick structures in the District, you’ll start to notice metal stars or “Xs” attached to the brick facades. Though sometimes mistaken for being purely decorative, these anchor plates serve a structural purpose. As their name suggests, these stars help anchor the brick facade of the Row to the interior wooden floor joists with long bolts known as tie rods. In the Row, there does not appear to be any formal arrangement for these tie rods.

Brickyards of the Hudson River

Though the Museum collection includes examples of earlier hand-made bricks, the majority are from the heyday of the Hudson River brick industry in the late 19th century. Brick making along the Hudson was initially done by hand but the introduction of steam-powered machinery revolutionized the business by the 1840s. As New York City expanded through the 19th century, the Hudson River brick industry grew to meet insatiable demand for building materials, with 135 brickyards in its heyday. By 1883, the area around Haverstraw, New York, alone had 41 brickyards that employed an estimated 2,400 men. The workers of these brickyards were largely Italian and Irish immigrants in the late 1800s; however by the 20th century, nearly 60% of the workforce was made up of African Americans, many of whom had travelled during the Great Migration to join the already extant Black community.

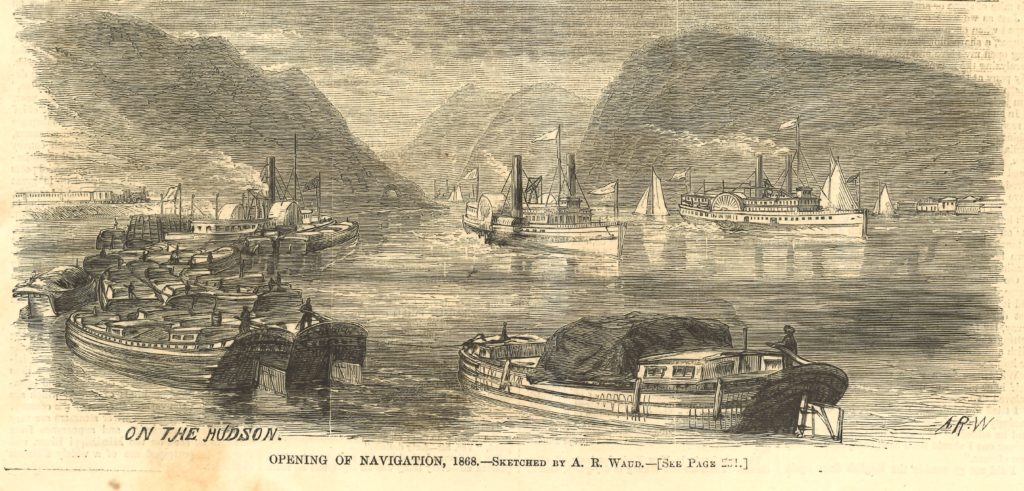

Alfred R. Waud (American, 1828-1891) Harper’s Weekly, publisher. “Opening of Navigation, 1868”, April 18, 1868. Paper, ink. Museum Purchase 1992.002.0010

Mechanization changed how bricks were made and a 1905 article in the Building Trades Employers’ Association Bulletin identified 78 distinct operations required in the production of bricks, from cutting sods of clay from the bank, to moulding, to levelling, to striking, to firing, to loading onto a barge to sail down the Hudson River to market in New York City. The article notes that despite the labor and manufacturing and transportation infrastructure invested into each brick’s creation (which I couldn’t summarize in just this one blog post!), bricks were relatively inexpensive:

“…taking the price current of common brick in New York at present ($10 per thousand), all this is done for each brick, practically at the cost of one cent.”[1] “The Rose Yards” Bulletin, Volume 6, published by Building Trades Employers’ Association by Charles Elley Hall, 1905, p. 134.

The fun thing is that bricks from this period were often impressed with the names of the makers, allowing us to trace where many of the Museum’s bricks originated:

Left: Rose Brick Co., manufacturer. “Brick”, late 19th century- early 20th century. Clay. South Street Seaport Museum, New York 1989.032.0005

Right: Arrow Brick Co., manufacturer. “Brick”, ca. 1910. Clay. South Street Seaport Museum, New York 1989.032.0027

The Rose Brick Company was one of the largest brickyards on the Hudson River. To put it into perspective, in 1905 Rose produced 75 million bricks. John C. Rose, the company’s founders, had been involved in the Hudson River brick industry starting in 1866. At the company’s height, there would be 40 to 50 barges holding 12 to 15 million Rose bricks off the shore of Manhattan, waiting to be purchased. The Rose Yards themselves were known for being particularly concerned for the employees and their families living in the adjoining Roseton. The town- which included a school house, club building, reading room, and churches- was naturally built with Rose bricks.

The Arrow Yards on Danskammer Point, owned by Edward Maitland Armstrong, opened in 1905. The name of the brickyard came from the arrowheads that the workers found while starting to mine the claybeds. Interestingly, the owner’s father, David Maitland Armstrong, mentioned the negative environmental impact of brickyards like Arrow in his memoirs, reminiscing in the early 19th century, “…before the brick-yards came, scarring the landscape and even gnawing away our lawns and gardens, the situation was beautiful, crowning a wooded plateau, with a sweeping view across Newburgh bay to the Highlands.”[2] “Day before yesterday; reminiscences of a varied life” by David Maitland Armstrong, 1920, p.4.

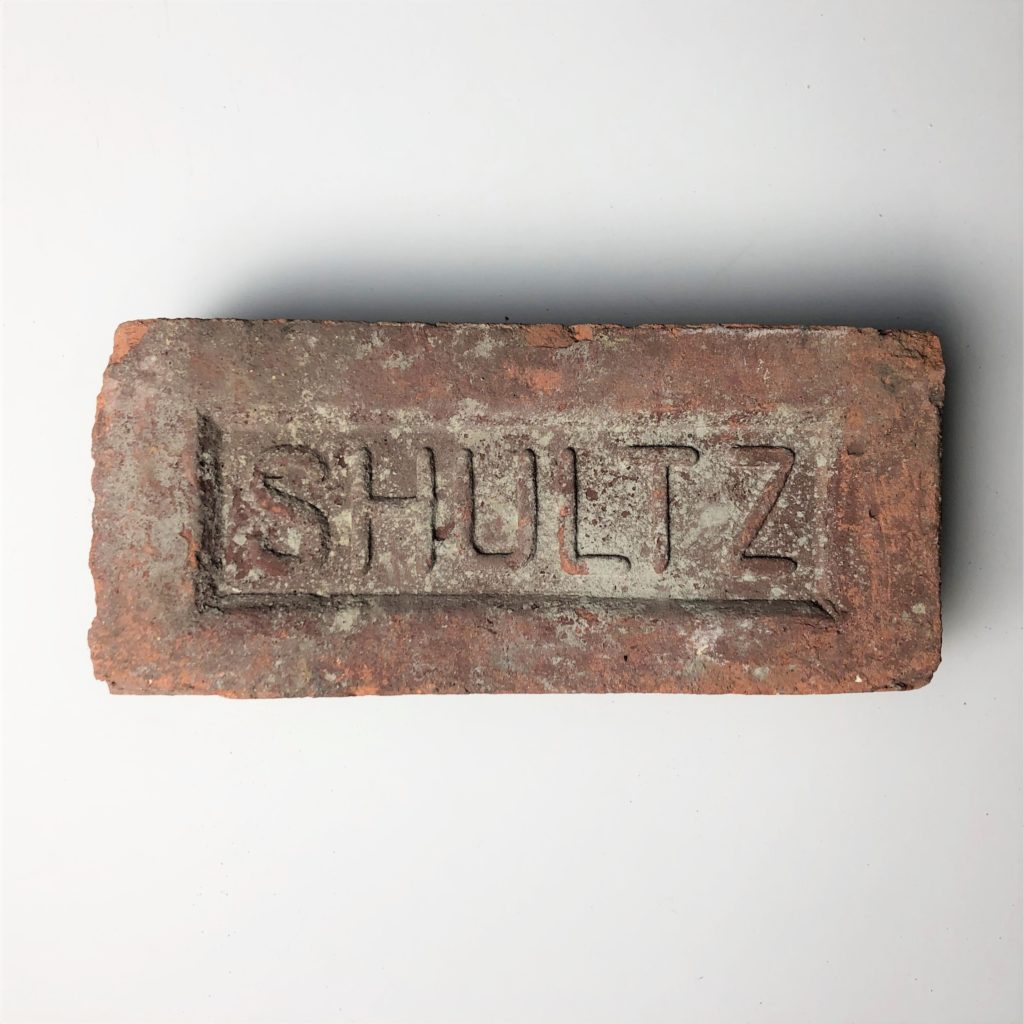

Left: The Shultz Brick Co., manufacturer. “Brick”, late 19th century- early 20th century. Clay. South Street Seaport Museum, New York 1989.032.0015

Center: Cary Brick Co., manufacturer. “Brick”, early 20th century. Clay. South Street Seaport Museum, New York 1989.032.0010

Right: Empire Brick and Supply Co., manufacturer. “Brick”, early 20th century. Clay. South Street Seaport Museum, New York 1989.032.0001

The Shultz family started their brick business in Keyport, New Jersey, but moved to East Kingston, New York, in 1876 to take advantage of the opportunities along the Hudson River. The Shultz Yard originally used horses to power their machinery but switched to steam in 1878. By 1905 the plant was burning 100 tons of coal per million bricks produced. Just as barges carried the finished bricks down the Hudson to the Port of New York, barges would transport the vast amount of fuel needed by the brickyards upriver.

The Cary Yards were unique; with two yards over 30 miles apart in Newton Hook and Cohoes, the Cary brickworks operated year-round as opposed to seasonally. This allowed the Cary brickyards to both promise reliability in meeting their contracts and to retain some of the most skilled brick workers in the regions as their employees were guaranteed a steady income.

Empire Brick and Supply Company (originally the Walsh Brickyards) had their main brickworks in Stockport but also had several facilities throughout New York City. In 1907, aside from their main offices on Broadway, Empire had yards and storage on the West Side at Leroy St. and 47th St.; on the East Side at 150th St,., as well as two locations in Brooklyn and another in the Bronx. This allowed them to easily take large jobs throughout the city.

“View of Piers 68 and 69” November 1910. Photographic paper. Gift of William Asadorian, South Street Seaport Museum Archives H45-0076

This 1910 photograph shows stacks of Empire bricks for sale unloaded near Piers 68 and 69, Hudson River. Barges and piles of other building supplies, like lumber, can be seen in the background.

By the late 1920s the rise in concrete construction, along with competition from other regions, caused the Hudson River brick industry to decline. The Great Depression and disruptions caused by World War II hastened the closing of brickyards. One of the last brickyards, the Hutton Brick Company which had operated since the 1870s, closed in 1980.

However, the remains of this major industry can still be found along the Hudson, with projects like the The Hudson River Brickyard Trail and the Haverstraw Brick Museum dedicated to highlighting this New York story. Of course, New York City is also, in part, a monument to the work done at hundreds of brickyards, even though the ships and barges that once brought these building materials to the growing metropolis have long since vanished.

Additional readings and resources

“History of the Clay-working Industry in the United States” by Heinrich Ries and Henry Leighton, 1909, pp. 146-160.

“Brick Construction” in The Schermerhorn Row Block: A Study in Nineteenth-Century Building Technology in New York City Stewart et. al. 1981, pp. 37-41.

“Resources of the Hudson River Valley” by Norman Brouwer, published in Seaport magazine, Winter 1986, pp. 13-19.

“Inside the Long-Lost Brickyards That Built N.Y.C.” by Devorah Lev-Tov, published on New York Times, May 21, 2001.

“Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic” by Fiske Kimball, 2001.

“Historical Perspectives of the African Burial Ground New York Blacks and the Diaspora” by Edna Greene Medford, 2009.

“African American History Showcased in Village of Haverstraw” published by Rockland County Times on October 10, 2017.

References

| ↑1 | “The Rose Yards” Bulletin, Volume 6, published by Building Trades Employers’ Association by Charles Elley Hall, 1905, p. 134. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Day before yesterday; reminiscences of a varied life” by David Maitland Armstrong, 1920, p.4. |